The bridge Natural gas's crucial role as a transitional energy source

February 2025

February 2025

Over the past 25 years, demand for natural gas has surged by 80%, to the point where it now meets almost a quarter of the world’s energy needs. Its success lies in the scale of global resources, its low production costs, ease of storage and dispatch, and comparative environmental advantages.

Gas’s primary role in accelerating the energy transition ‒ displacing highly polluting coal and supporting the expansion of renewables in the power sector ‒ cannot be underestimated. Meanwhile, in the transport sector, liquefied natural gas (LNG) is rapidly replacing diesel in China’s trucking sector and competing with fuel oil in global marine bunkering. Gas will also remain fundamental to numerous industrial processes and residential heating for years to come.

Of course, gas has its critics. Some dismiss its value as a transition fuel, denouncing it as just another fossil fuel driving the climate crisis. Emissions from gas, particularly LNG, have been in the spotlight like never before, with some justification. What’s more, gas is not cheap. Delivered LNG costs remain high, and without a meaningful carbon price, gas cannot compete with the price of coal in powering Asia’s booming economies. Add to that, as Russia’s war on Ukraine has demonstrated, an over-reliance on gas imports from a single source does not constitute a robust energy security strategy.

Faced with these challenges, gas needs to demonstrate its true value ‒ as a reliable, affordable and flexible fuel of the future and as a lower-carbon solution that will help deliver, not hinder, the energy transition as alternative technologies strive to reach critical mass.

In a world seeking greater access to clean, reliable and affordable energy, making the case for gas has never been more pressing.

The case for gas

As energy demand grows around the world, gas and LNG will be critical in the shift to a lower-carbon future. Surging electrification, increasingly met by renewable power sources, will lead the charge to curb CO2 emissions. Electrification can only move so fast, however, and the adoption of emerging low-carbon technologies, such as hydrogen, is currently too slow to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. With coal still accounting for 30% of the world’s energy needs, shifting to gas as a transition fuel is a compelling option.

The cleanest fossil fuel

The lower environmental impact of burning natural gas rather than other fossil fuels is clear . Burning gas produces only half the carbon dioxide (CO2) of coal and 70% of oil. It does not produce sulphur dioxide (SOx) or mercury and emits only a fifth of the carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides (NOx) produced by coal. Much of the 12.6% cut in US CO2 emissions and the 45% reduction in air pollution in Beijing (that is, PM2.5 and NO2) from China’s “blue sky” policies over the past decade have come from a shift from coal to gas.

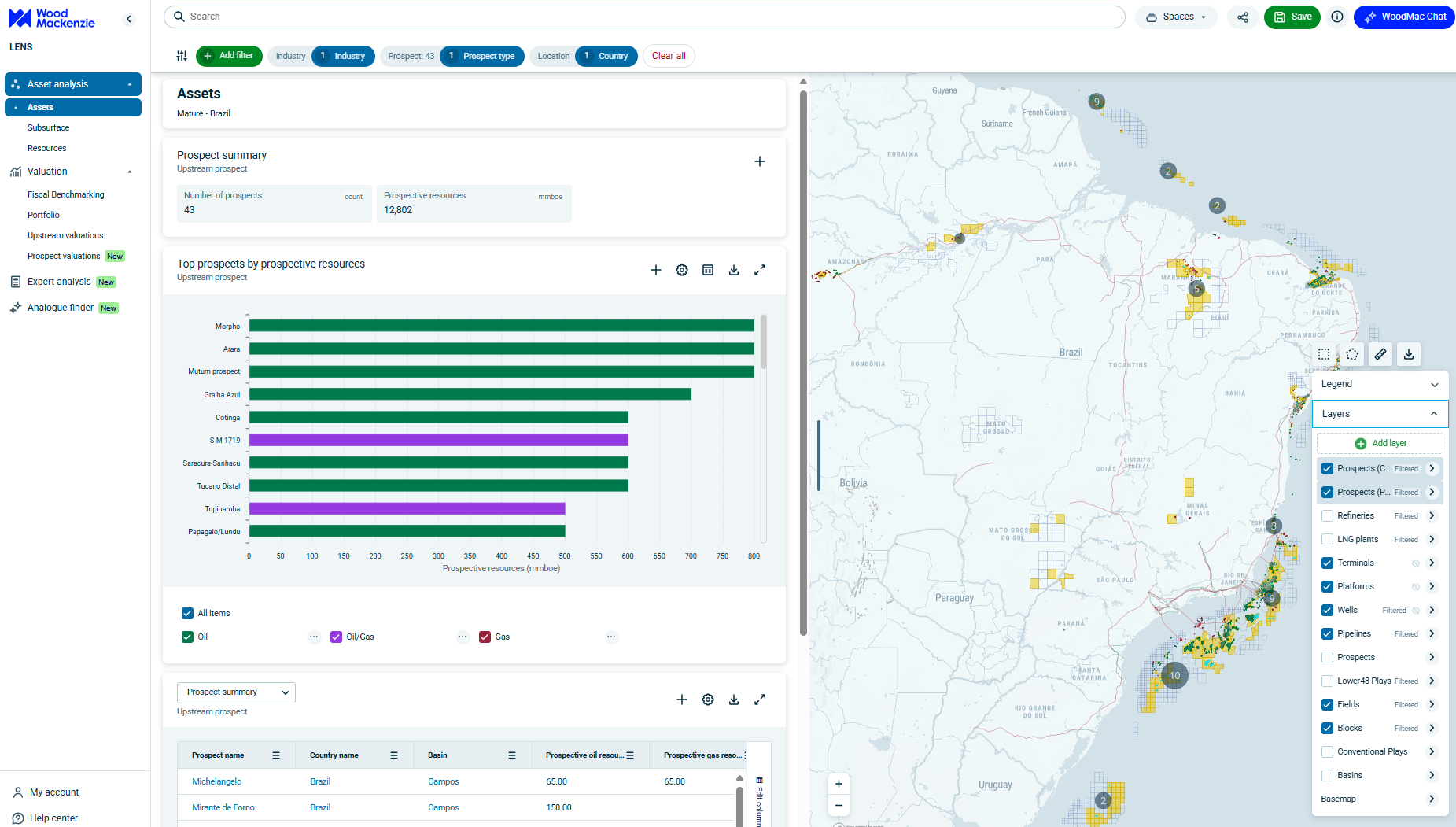

Source: Wood Mackenzie Energy Transition Service, Lens Gas & LNG

Reliability and flexibility

Power generators around the world are hungry for more gas, albeit for different reasons. In the US, gas’s reliability is seen as key as the artificial intelligence (AI) revolution and industrial reshoring are transforming electricity markets, boosting power demand by up to 3% a year. The dramatic increase in US baseload power demand provides significant upside potential to US gas demand, a shift that could be replicated globally as data centres emerge as national security assets.

In Europe, where investments in renewables continue apace, governments are supporting more gas-fired plants to ensure they have sufficient reliable and flexible capacity to cope with renewable intermittency and seasonal needs.

In Southeast Asia’s major economies, LNG is the only immediate baseload option for meeting surging electricity demand without increasing countries’ dependence on coal. Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines have set ambitions that could see up to 180 GW of new gas-fired plants being built by 2050.

High LNG prices since 2022 risk undermining the full potential of wider gas adoption in Asia, however. In China and India, where gas usage is mainly used , gas demand is still expected to grow by 95 bcm through to 2050 in the power sector, offering the most practical option for ensuring flexibility as renewable investments surge. Without a carbon price of around US$100/tonne, reducing China and India’s dependency on baseload coal looks like a massive ask. The prize, however, would be a reduction of more than 325 Mt of CO2 and result in additional gas demand of up to 173 bcm by 2035.

Source: Wood Mackenzie Lens Power

Enabler of emerging lower-carbon technologies

Natural gas can also act as a catalyst for the advancement of other lower-carbon technologies, including carbon capture and storage (CCS) and low-carbon hydrogen.

CCS is key to reducing emissions in hard-to-abate industries, such as fertiliser, steel and cement, where electricity has limited applicability because of the high heat required in the industrial process. With appropriate carbon prices and subsidies, CCS offers a compelling approach to reducing emissions. Combining CCS with gas in the power sector has the potential to reduce carbon emissions considerably.

Gas-fired plants provide greater operational flexibility and require less CO2 management and storage capacity per MWh of power produced than coal-fired plants with CCS, supporting the shift towards more renewable capacity. Recent investment decisions provide momentum across the US and Europe, where generous subsidies and carbon prices are available. But CCS hubs must also be accelerated across Asia. With the right policies and incentives in place, up to 2.2 Bt of CCS could be developed across sectors by 2050 globally.

Successful CCS is also needed to accelerate the development of low-carbon hydrogen. Blue hydrogen, produced using natural gas and CCS, has a higher carbon intensity than green hydrogen, produced by water electrolysis using renewable power. However, with the cost of blue hydrogen now considerably lower than that of green hydrogen, it will be instrumental in driving early developments and demand. Almost double the amount of low-carbon hydrogen projects currently in operation or under construction are blue, and Wood Mackenzie forecasts more than 40 Mt of blue hydrogen capacity to be developed by 2050.

Longer-term gas alternatives

Low-carbon gases, such as biomethane and e-methane, are promoted as net-zero, drop-in solutions that limit investment costs by using existing gas and LNG infrastructure. Biomethane, derived from biogas produced from organic waste and agricultural feedstock, is expensive but is emerging as an alternative to natural gas in several markets.

Generous subsidies are encouraging production predominantly in the US and Europe, although countries in Asia Pacific are also starting to capitalise on their abundant agricultural feedstock. Wood Mackenzie sees a modest biomethane supply of 74 bcm by 2050, meeting just 2% or so of annual global gas demand. Penetration will be higher in European and North American markets, however, reaching almost 6% by mid-century, which could prove conservative if more capacity is added.

E-methane, produced by combining green hydrogen with CO2 from biogenic or direct air capture, is an option for transporting hydrogen to remote locations, although prohibitively high production costs weigh on its future scalability.

Gas will not be an easy sell

Still a 'dirty' word

Gas and LNG are substantial greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters. Recent claims that the LNG value chain is more GHG-intensive than coal are unfounded, in Wood Mackenzie’s view. Our analysis shows that, on average, LNG has around 60% lower GHG intensity than coal. Even when considering a 20-year global warming potential (GWP) and comparing methane-intensive LNG with coal burnt in highly efficient plants, LNG is still 26% less GHG-intensive. Nevertheless, its carbon dioxide and methane emissions need to be addressed as a matter of urgency to ensure its primacy as a bridging fuel.

Efforts to reduce methane emissions are gathering pace, particularly in the US where developers are securing growing volumes of certified gas. New LNG projects are now using technologies to limit their emissions footprint, including adopting electric drives and pre-combustion CCS. However, the industry’s primary problem is the unchecked emissions from existing plants, as retrofitting electric drives or post-combustion carbon capture remain uneconomic. With buyers reluctant to pay more, major investments have stalled. Failure to address these issues will be detrimental to gas’s position as an energy transition ally.

Notes: LNG: upstream, transmission liquefaction and shipping emissions calculated as global average, weighted based on nominal capacity. Gas fired power plant assumed at 55% efficiency. High and low LNG emissions refer to location of emission intensity of LNG only. Coal: mining, transmission and shipping emissions calculated as global average of supply and trade. Coal fired power plant assumed at 36% efficiency. High and low emissions refer to both coal type (e.g. bituminous, lignite, etc.) and coal plant capacity efficiency (from 30% to 42%).

Source: Wood Mackenzie LNG Carbon Emissions Tool and Emissions Benchmarking Tool

LNG affordability remains an issue

LNG will never be cheap. Prices will be set by the cost of developing new supply. With US projects likely the marginal cost supplier for the foreseeable future, global LNG prices are expected to increase over time as Henry Hub prices strengthen. Pressure on producers to decarbonise will compound this. Pairing gas-fired power plants with CCS to deliver close-to-zero emissions will push up electricity tariffs for consumers.

Affordability is LNG’s biggest weakness in Asian markets. The next wave of supply from 2026 will lower prices, but LNG will remain the highest-cost option for Asian power generators. Government support through power purchase agreements, deregulated gas prices and incentives for infrastructure can help, but without a massive – and unrealistic – hike in carbon prices, gas won’t reach its full potential.

OCGT: open-cycle gas turbine. CCGT: combined cycle gas turbine. PWR: pressurised water reactor. PV: Photovoltaic

Source: Wood Mackenzie Lens Power

Low-carbon options are still nascent

While we are confident in the potential of low-carbon gas technologies such as CCS, blue hydrogen and biomethane to reduce GHG emissions, they all carry significant risks. These technologies are still in the early stages of development and require substantial technical and commercial progress before they can be scaled up. For example, the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) for combined-cycle gas turbines with CCS in Asia Pacific averages around US$250/MWh today, more than twice the LCOE of unabated gas generation.

Without policy support to drive the continued development of low-carbon gas technologies, it is difficult to envision rapid advancement and cost reductions. Consequently, nascent technologies face delayed deployment or, worse, fail to materialise.

Horizons Live: replay

At Horizons Live, this month's authors debated key points from the report and tackled questions in an audience Q&A.

Missed it?

Gas, LNG & The Future of Energy Conference

Join us from 2-3 June 2026 in London for expert industry insight on the challenges and opportunities for the sector.

Explore our latest thinking in Horizons

Loading...

Why sign-up?

By submitting your details you’ll gain access to the latest Horizons report, part of a thought-leadership series exploring the themes shaping the energy natural resources landscape. You’ll also receive the Inside Track, our weekly newsletter, so you won’t miss out on future editions.